So many communities ... so little time. What makes a community successful? by Kevin Jarrett

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

{Cross posted on Welcome to NCS-Tech!}

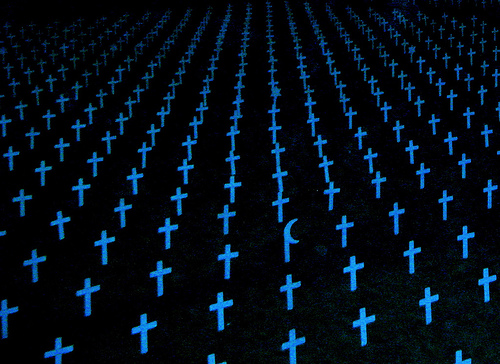

photo credit: antwerpenR

"Come join me on [INSERT NAME HERE] Community" We've all gotten these messages before ... those usually ubiquitous urgings to join an online space, most of the time, "Nings" (social networks hosted at Ning.com). Some are more relevant to our needs and interests than others. Some are just for fun. Sometimes, we're even on the other end, inviting people to join communities WE have created. So there's no shortage of networks for us to join. There's only one problem: like the person pictured above, we're overloaded. "Ning"-ed out. Hyper-connected/over-extended. Overwhelmed with choices. And yet, we rely on many communities - a select few become a regular part of our daily learning, spaces we rely on for information from and connection to people we admire and respect. But for other networks, it's a different story. Maybe we'll visit the community in question, see if anyone we know has joined, take a look around, maybe even update our profile page or make a forum posting or two. But ... after that ... what will make us return again and again, drawn back by the quality of the dialog, the value of the resources shared, the variety of opinions, the sense of belonging the emanates from the virtual space? So, I've been wondering ... What makes a community successful? Let's start with what NOT to do. (I should know, I've seen - and built - plenty of failed networks. How about you?)

photo credit: kevindooley

Mashable's recent article, 8 Things to Avoid When Building a Community, is helpful. These eight insightful tips could effectively document the downfall of many communities. Either by action or inaction, such communities go from euphoria at launch to a slow, painful death - moslty when participants don't feel valued or acknowledged. They're not going to share opinions freely when there isn't much continuity between conversations and participants. There needs to be depth in posted content as well. All that said, great networks don't try to be all things to all people, they know their charter / target market / participant demographic and what matters to them. Leaders aren't appointed, they emerge organically. Failing to keep a steady stream of new material also contributes to the downfall of an embryonic community. For more, see the article, it's excellent and a quick read. Fortunately, Mashable also provides us with "10 Rules for Increasing Community Engagement," the yin to that other post's yang. A powerful tit-for-tat counterpoint (I know, one has 8, the other 10, work with me here...), its examples seem obvious at first glance - but if you've ever built a community, you know these tips are "easier said than done." Reading through the list, the message is clear: communities are PEOPLE!

photo credit: luispita.com

Whether it's the content people are creating that's lauded, or their arrival into the network, or their ability to personalize their space to reflect who they are, it's all about them. Making the network easy to use - no small feat with software as sophisticated as Ning - is crucial. I have a substantial personal interest in this topic. I helped create a community for our school, a Ning, several months ago. It's doing okay. We have a great membership rate - 80 to 85% of our staff has joined. (Far fewer participate regularly, but more about that later.) I'm also helping the New Jersey Department of Education and our EIRC develop an online presence for 33 Professional Learning Community (PLC) Lab Schools in our state. Our face to face meetings were terrific, but there seemed to be an opportunity to use technology to unite the group when we were back in our districts. But, instead of running off half-cocked and building something we thought people wanted, we did something radical - we actually asked them:

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

"Consider all the work you and your team does as a PLC Lab School. Reading, brainstorming, discussing, sharing files and resources, asking and answering questions, preparing for our periodic face-to-face “all-hands” meetings, etc. If we created an online community that made those activities easier and more meaningful, would you be interested?"

On a scale of 1-5, with 1 indicating the strongest positive response, 77% (55 out of 72) chose option 1 or 2. [Interestingly, 4% (3 people) actually voted no.] We went on to ask what kinds of things they'd want to do - or not do - in the community. Again, the responses were overwhelmingly positive - but we did identify some features/capabilities that were surprised to see weren't desired. This information will be crucial for us as we design the community, with the help of people who volunteered to be a part of the process. To me, anyone creating (or managing) a community has to answer this question:

What is the problem your community is trying to solve?

We have to remember that these communities are WORK. They are WORK for those of us who create and manage them and they are WORK for the people who participate in them. Any community that is perceived as CREATING MORE WORK for its members is NOT going to be successful long-term. On the other hand, communities that REDUCE the amount of WORK people have to do (by IMPROVING their professional EFFICIENCY) have a much greater chance of sustained success. Fortunately, there are lots of examples. One is Classroom2.0:

http://www.classroom20.com/ may not have been the first but it has clearly grown the fastest, boasting nearly 36,000 members as of this writing. Steve Hargadon was in the right place at the right time, creating a community that has drawn educators from the world over, into a community so massive that almost 500 "groups" (sub-areas) in the site are now active. Steve expertly guided Classroom 2.0 through its explosive growth as a personal learning network (PLN) for many of us. The problem he sought to solve? I've never asked him, but I'm willing to bet the answer has something to do with the professional and personal isolation that all teachers often endure. http://www.classroom20.com/ has helped end that isolation. Successful sites like http://www.classroom20.com/ are sometimes too big to grasp at a high level. When starting a smaller network, like the Ning at my school, trends are easier to spot. For example, the same people tend to be posting all the time! This bugged me until I read "Participation Inequality: Encouraging More Users to Contribute" by Jakob Nielsen. The article cites Will Hill's "90-10-1 Rule:"

...which is research done in the early 1990s, well before Web 2.0 and Nings and social networking came on the scene. In fact, human behavior in Nings remains unaffected by technology. People are people. They will do the same things they've done in electronic communities since we had the first opportunity to connect with each other online. Now it all makes sense. This is almost exactly what we are seeing in our Ning. Who knew it was what we should have expected all along? To wrap this up ... though I still have a lot to learn about communities, I feel better prepared today to help grow the ones I am responsible for, and participate more effectively in the ones I choose to belong to. I also have a better sense of what is needed to create a successful community, and with luck, will be able to help the PLC Lab Schools initiative build a something meaningful and advance our work together. And for that, I have to thank the many communities I've become a part of over the years. They've taught me more than any "formal" education I've ever had! Hope this helps, -kj-