Learning Loss, Trauma, and Our Window of Tolerance

Everyone has experienced trauma throughout the pandemic, so we need to acknowledge and work through it to establish a strong foundation for learning

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As we start the school year in whatever learning environment your district or school is in, there’s a great deal of emphasis and pressure on students and educators related to learning gaps and loss from the spring. However, from a trauma-informed research and mental health perspective, concentrate on well-being first. We all have experienced trauma in so many different ways throughout this pandemic, so to establish a strong foundation for learning, we need to acknowledge and work through it.

Dr. Dan Siegel of UCLA’s Mindful Awareness Research Center defines trauma as “an experience we have that overwhelms our capacity to cope.” Recent research in neuroscience finds that trauma is stored in our bodies and needs movement in order to work through and understand the effects on our body, mind, and psyche. Additionally, educators can suffer secondary traumatic stress from working with students through their trauma.

Trauma can manifest itself in children in a multitude of ways. For young children, they could experience fear of strangers and separation anxiety, have trouble eating or sleeping, or regress after hitting a developmental milestone. For school-age children, they may engage in aggressive behavior, become withdrawn, or exhibit difficulty concentrating in school. For adolescents, they may be anxious or depressed, feel intense guilt, anger, and shame, or in a worst case scenario, experience thoughts of suicide.

When children exhibit these behaviors, we as educators can sometimes forget about taking the time to understand the root cause of the behavior and trying to help the child rather than see them as being “difficult” or “bad.” As Bessel van der Kolk, a Professor of Psychiatry and President of the Trauma Research Foundation, states in his book The Body Keeps the Score, Brain, Mind and Body in the healing of Trauma: “When children are oppositional, defensive, numbed out, or enraged, it’s also important to recognize that such ‘bad behavior’ may be repeat action patterns that were established to survive serious threats, even if they are intensely upsetting or off-putting.”

Polyvagal Theory

Dr. Stephen Porges introduced the Polyvagal Theory to help us understand our response to trauma and stress, and can serve as a foundation for creating trauma-informed learning environments. This theory is based on the vagus nerve, which touches upon every major system in our bodies, and its health is essential to caring for our nervous system.

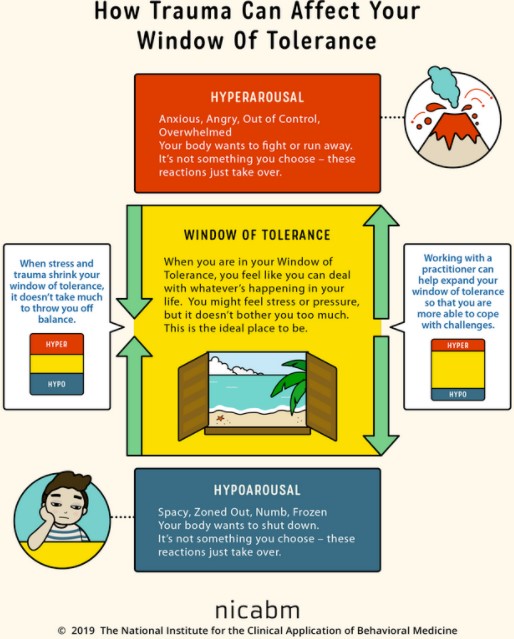

The Polyvagal Theory puts focus on our window of tolerance, which you can see below in the image from the National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine. When we are triggered, we are outside of our window of tolerance. When we are numb, feeling hopeless, we are also outside of our window of tolerance. In these two spaces, no new learning can take place.

Let’s repeat that, and let it sink in. No new learning can take place when we are outside of our window of tolerance. Only within our window of tolerance can new learning take place, which brings us to why understanding these concepts is so vitally important to the field of education, especially where we are today in post-pandemic learning. Van der Kolk emphasizes, “After trauma, the world is experienced with a different nervous system.” Trauma changes our ability to adapt based on what it leaves behind in our physiology and nervous system. As learners, we want to get to a place where we feel a sense of safety in our bodies and learning space.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

Start with Self Care

One of the most important things that we can do for ourselves and our students who have experienced trauma is give space to process and as emphasized in Permission to Feel, Marc Brackett’s new book. Oftentimes, we are told to not feel our emotions (emotional bypassing), to think positively instead (toxic positivity), when in reality, we should be processing emotions so that they don’t come up for us later. The ACES (Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale) reports that among 17,421 patients, childhood trauma correlated to serious adult medical conditions. Dr. Vincent Felitti, the Director of the ACE Study, shared, “Contrary to conventional belief, time does not heal all wounds, since humans convert traumatic emotional experiences in childhood into organic disease later in life.”

We as educators need to remember the Four Rs of trauma-informed care. We need to realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand potential paths for recovery. We need to recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in our students and others involved in the learning process. We need to respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into our school and classroom procedures and practices. And we need to resist re-traumatization of children, as well as the adults who care for them.

Some key trauma-informed SEL practices include (but are not limited to) creating predictable routines, building strong and supportive relationships, empowering students’ agency, supporting the development of self-regulation skills, and providing opportunities to explore individual and community identities.

Additionally, through mindfulness practices, we can grow our windows of tolerance so that we are better able to cope with challenges. With meditation, yoga, Qigong, and Tai Chi, for example, you can work with your students to move and help them build their window of tolerance and help change the physiological states left behind by trauma. Tying this to social-emotional learning, Bessel van der Kolk shares in his book that our own internal systems, when trusted by ourselves and those with whom we interact, can help us heal: “Give people greater access to their innate self-regulatory systems - the way they move, breathe, sing, interact with one another - so they can discover their natural resources to regulate themselves in a different way, especially when life gets challenging...The last things that should be cut from school schedules are chorus, physical education, recess, and anything involving movement, play, and joyful engagement.”

These practices help us work through our traumas, to become comfortable with being in the present moment and being able to stay embodied rather than to disassociate, which is a common practice for trauma survivors. It can help us to feel the places that have no words.

We acknowledge that we as educators are stressed. We were stressed pre-COVID, but then went into absolute emergency crisis mode to continue to serve our students, their families, our schools and districts, and our communities. And we did this on top of also taking care of our own families as well. This has been an extremely traumatic time.

Practice self compassion and be gentle with yourself and everyone around you. Engage in grounding practices on a regular basis to keep yourself healthy for yourself and those around you. Remember to fill your own cup first so you can fill the cups of others.

About the Author

Dr. Kennedy is an educational researcher and consultant. She has focused on the areas of K-12 online, blended, and digital learning for over 15 years as well as SEL for teachers and students, in addition to healing trauma through somatic approaches for over five years. Most of her work in these areas centers on research to practice. In addition to her consulting work, she owns and operates Wellness for Educators, which centers around the importance of well-being of educators. Through somatic approaches, including but not limited to yoga, Qigong, Tai Chi, as well as contemplative, reflective practices such as meditation and mindfulness, and other therapeutic modalities (cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT), EMDR, etc), the tissues that hold traumatic experiences, such as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), have the potential to be healed. Using her own personal experience with severe ACEs, Dr. Kennedy and her team provide strategies, professional learning, and other opportunities to educators so they can empower themselves to work with their own traumas, secondary traumatic stress, and emotions so that they can heal and better be there for their students as well as help their students empower and heal themselves.

Additional Resources

American School Counselor Association Virtual High School Counseling - Resources, lessons and links for providing online student support

CASC & WSCA Educational Resources for Virtual School Counseling - Takeaways and resources from a recent virtual school counseling webinar from the California Association of School Counselors