Teaching About the James Webb Space Telescope

The James Webb Space Telescope provides lots of opportunities for teachers to engage and inspire their students.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Telescopes are time machines.

This may be a trope but it’s also true, says Klaus Pontoppidan, a James Webb Space Telescope Project Scientist.

“Literally all telescopes are time machines,” he says. “Light is traveling at a finite speed, and so if you look at the moon, it is taking one second for the light to get from the moon to us, and we're seeing the moon as it looked one second ago.”

The James Webb Space Telescope has the ability to see back in time 13.6 billion years to when the universe was in its infancy, making it the most powerful tool for peering into the past ever produced by humanity. This is one of the reasons the James Webb Space Telescope is a wonderful teaching opportunity and a great way to get kids engaged and excited about science, astronomy, and STEM.

Below are tips on incorporating discussion about the James Webb Space Telescope discussion into your class. In addition, teachers will want to read our Best NASA Resources for Teaching About James Webb piece.

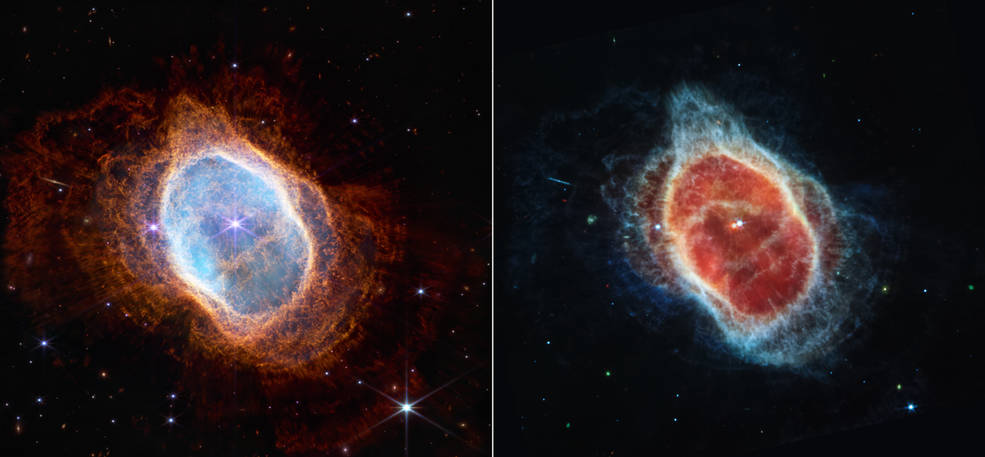

Share James Webb Space Telescope’s Images With Students

The first images released from the telescope are a perfect jumping-off point to engage with students, says Christine Anne Royce, Ed.D, co-director of MAT in STEM Education at Shippensburg University.

“Today's students are very visually oriented,” says Royce, the past president of the National Science Teaching Association. “They like to see the pictures, they like to see the illustrations, it helps to make connections for them.”

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

“We can start to talk about astronomy concepts. ‘What is the Webb Space Telescope observing? What are we seeing?’” she adds.

The Birth of Galaxies

One of the goals of The James Webb Space Telescope is to study the early moments of the universe and the formation of stars and galaxies. Its first images have already started to shift perceptions. “We see very, very early galaxies that already have fully formed discs [and] uniform structure,” Pontoppidan says. “The thought was always that very early galaxies start out really, really small and very irregular.”

This unexpected find, if it holds up to further research, means scientists will need to create new models for the early universe to explain how this symmetry is possible. Having students examine these types of questions can be a great way for them to learn about the scientific method and how new understanding emerges.

The Age of Light

To determine how far back in time James Webb is looking, scientists determine the age of light by measuring its wavelength. Science teachers can delve into how this is accomplished or discuss the implications of looking into the universe’s past more broadly.

For example, the Hubble Space Telescope can look back 13.4 billion years. The James Webb Space Telescope, which is an infrared telescope, can look back an additional 200 million years. This may sound like a comparatively small number, Pontoppidan says, but it is a crucial jump. “It's really making a step from having seen galaxies that are [in] maybe elementary school and middle school, to actually going all the way back to their birth and early very formative toddler years where they learn to be galaxies,” he says.

Working with Younger Students

For younger students, Royce suggests simply sharing James Webb’s images and asking students what they see. “Young kids have great creativity,” she says. “When you're looking at the pictures, they start to talk about what they see, ‘Oh, that looks like…’ and they give you a description. Often that's exactly how some of these more conventional names are given to objects.”

For instance, the Horsehead Nebula in the constellation Orion is named for its resemblance to a horse’s head. With the James Webb Space Telescope images, there is a discussion of the “mountains'' and “valleys” seen in the star-forming region of the Corina Nebula.

The Search for Extraterrestrial Life

Regardless of their age, Pontoppidan says many students will likely be most interested in the role the James Webb Space Telescope will ultimately play in the search for other planets that could potentially sustain life. This is a good opportunity to discuss what causes a blue sky on a planet and what conditions are favorable to the presence of water and by extension life, as well as the mind-boggling vastness of the universe.

“You look at the deep field image and every single spot in there is a galaxy,” he says. ”We know today that every star typically has at least one planet. So billions of galaxies, billions of stars. How many potential worlds is that?”

Erik Ofgang is a Tech & Learning contributor. A journalist, author and educator, his work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Associated Press. He currently teaches at Western Connecticut State University’s MFA program. While a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine he won a Society of Professional Journalism Award for his education reporting. He is interested in how humans learn and how technology can make that more effective.