How to Teach Data Science in K-5

It’s never too early to start teaching students about data science, say experts

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It’s never too early to start teaching data science to kids.

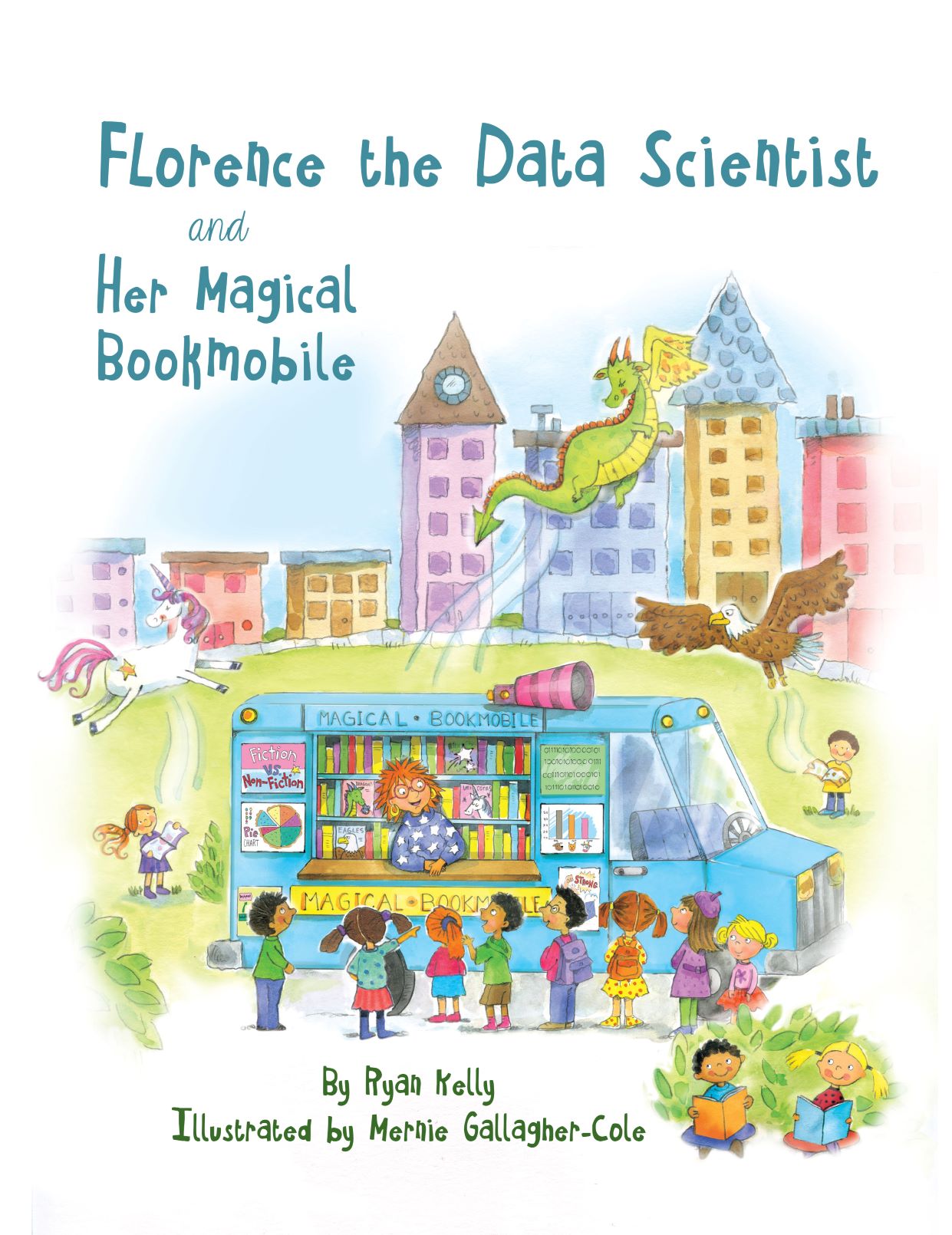

That’s the message from the National Science Teaching Association. In honor of April being Mathematics and Statistics Awareness Month, the organization has partnered with the Domino Data Lab to release a classroom-ready data science lesson plan for K-5 educators. The lesson plan supports Florence the Data Scientist and Her Magical Bookmobile, a new children’s ebook from Domino Data Lab written by Ryan Kelly and illustrated by Mernie Gallagher-Cole, which is geared to children aged 6-8 and free for educators and their students.

Tricia Shelton, NSTA’s chief learning officer, discusses how to utilize the new resources and best practices for elementary school teachers to teach data science.

Get Students Thinking About Data Science Early

“If we can get kids to start thinking about how they can collect data, how they can analyze data, how they can harness the power of data to develop solutions to problems in the classroom setting early on, then as they progress up through K-12 education, we can expand on that developing knowledge and skill set,” Shelton says. “They can start to tackle more complex problems, more societally pressing problems. And even though kids might not be the ones who are solving those problems, there's power in the classroom when they can act and think like scientists and engineers, as those in the STEM field do.”

Starting with young students allows teachers to build those multidisciplinary competencies over time and exposes students to potential opportunities later in life. “They can see themselves in those careers and in the places outside of school where they could have an impact,” she says.

Utilize Free Resources for Teaching Data Science

NSTA’s recently released data science lesson plan walks educators through how to teach students to use data to predict the length of their shadows. For example, there is advice for encouraging students to wonder and speculate about the length of their shadow and record their predictions. Then the lesson plan describes how to have them actually measure shadow length at various times of the day using common classroom items such as chalk and measuring tape. The students can then compare data, look for patterns in the data, and create graphs to predict shadow length in the future.

At the conclusion of the lesson there are tips for incorporating Florence The Data Scientist and Her Magical Bookmobile. The book is a fun way to have children extend the lesson and further explore the possibilities of data science.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

The lesson is designed to show students how to recognize patterns and make predictions about shadow length and to realize that the same type of thinking and data analysis can be used to make predictions in all kinds of examples in the real world. “And this is what data scientists do,” Shelton says

This lesson on shadow length is part of NSTA’s Daily Do, a collection of Next Generation Science Standards-aligned and grade-specific sensemaking tasks that educators can use to better engage students in scientific thinking.

You Don’t Need to Be an Expert to Teach Data Science

Teaching data science can be intimidating, even for a seasoned teacher. “They say to themselves, ‘What is data science? How could I possibly tackle data science in my classroom?’” Shelton says. But the Daily Do and the shadow lesson are designed to help educators navigate the process.

“What this lesson does is it shows them within their own data policy standards that there are actually pieces of the science and engineering practices,” Shelton says. “It is showing teachers a piece of the standards that in many areas is a little bit underutilized, and then giving them the guidance to be able to support that kind of reasoning and thinking in analyzing the data in order to make predictions. The lesson itself has a lot of guidance for the teacher, so that they feel comfortable in entering into this realm.”

Erik Ofgang is a Tech & Learning contributor. A journalist, author and educator, his work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Associated Press. He currently teaches at Western Connecticut State University’s MFA program. While a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine he won a Society of Professional Journalism Award for his education reporting. He is interested in how humans learn and how technology can make that more effective.