Racism, Intolerance, and Teaching the Holocaust as a Current Event

There are lots of resources available that can help.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I’ll be honest. I’m having trouble processing the recent hate inspired events in El Paso, Texas and Dayton, Ohio.

But one thing that has become clear to me over the last few years is that the more we talk about racism and discrimination – starting with the fact that they exist – the better chance we have of combating their effects.

To ignore these shootings and the shooting attack on Oslo’s al-Noor Islamic Center four days ago and the June arson fires of three African American churches in Louisiana and the May arson attack on a mosque in New Haven, Connecticut and the March attacks on New Zealand mosques and last year’s attack on a Pittsburg synagogue and the 2017 demonstrations in Charlottesville and the 2015 African American church shooting in Charleston and all of the other too numerous to mention incidents . . . to ignore as teachers this pattern of violence – not to mention what is happening online – seems like educational malpractice.

Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe we shouldn’t teach our kids about what has and is happening in this country and around the world.

But I don’t think I am.

I think we have a responsibility as social studies teachers to give our kids the tools they need to make the world a better place. And part of that skill set has to include conversations about past and present intolerance. Is it easy? No. Can it be done. Yes. (You might try this, or this, maybe this, and I love this.)

Another way to create that skill set is to do a better job of focusing on the human stories of the Holocaust. I know that many of you teach the Holocaust and teach it well. But as you’re planning your nine month scope and sequence to include these sorts of conversations, would you mind if I share a few semi-random thoughts?

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

1. Be clear from the get go with your kids. It happened.

We have hundreds of thousands, millions, of primary sources. We have photos. Government documents. Train timetables. Movies. We’ve got oral histories. Diaries. Letters. Court transcripts. There are prison confessions. Newspapers. Lists of stolen property. Sacks of hair. Piles of shoes. Boxes of wedding rings. And many of the actual camps, barbed wire, gas chambers, and crematoria still exist.

So be clear.

The Holocaust happened. Over six million European Jews were murdered between 1933 and 1945. More than six million others deemed undesirable were also murdered by the government and party led by Adolf Hitler.

So, please, do not plan an historical thinking activity that asks your kids:

Don’t give students copies of or links to articles written by Holocaust deniers – in an attempt to be “unbiased” and open minded – and then ask them to use their analysis skills to determine whether or not 12 million people were murdered as a result of hate and prejudice. Don’t provide students the opportunity to use that “evidence” to support a claim that the Holocaust is a hoax.

I’ve never seen or heard of a teacher who asked their students if the American Civil War happened. Or if the 1929 stock market crash is a hoax. Whether or not George Washington actually won the battle of Yorktown. Or if he was our first president. I support the goal of encouraging historical thinking skills through the use of uncomfortable content. But not the clearly false equivalency of millions of primary sources documenting an event versus a few racist secondary sources that attempt to explain away 12 million bodies.

As we struggle to address the ongoing attacks and murder of American citizens and the rise of hate groups throughout the United States and around the world, we need to be careful how we go about our work. While talking about genocide in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s, we need to be very intentional about asking better questions. About using better evidence.

2. Focus on questions of why, not if, racist attacks happened and continue to happen.

The Holocaust took place because individuals, groups, and nations made intentional decisions to act or not to act. Focusing on those decisions can lead to insights into history and human nature and can help your students become better critical thinkers. So talk about the choices that people made and continue to make.

3. Ask questions of courage and perseverance.

Simply choosing to stay alive is a form of resistance. Writing a diary is a form of resistance. So talk about how both victims and rescuers resisted. And people who risked their lives to rescue victims of Nazi oppression do provide useful, important, and compelling role models for students. But be careful – only a small fraction of non-Jews under Nazi occupation actually helped rescue Jews, so an overemphasis on heroic actions during your unit on the Holocaust can result in an inaccurate and unbalanced account of the history.

4. Ask questions about bystanders and perpetrators.

Roles that people played during this time were very complex. One helpful technique for engaging students is to think of the participants as belonging to one of four categories: victims, perpetrators, rescuers, or bystanders. Examine the actions, motives, and decisions of each group. Portray all individuals, including victims and perpetrators, as human beings who are capable of moral judgment and independent decision making. Do the same categories exist today? What roles are being filled in 2019? By whom?

5. Ask questions about how kids should and can respond.

“Never forget” is one of the important messages kids can take away from reading things like Anne Frank’s diary. But we need to go beyond that to “individual decisions can have a tremendous impact.” Remembering is passive. Taking action means making a difference. Ask students “how will you respond now?” To the shooting in El Paso? In Pittsburg? To the rise of white nationalism in the US? To racist comments and behavior in your school? What options can you help students uncover?

6. There are lots of resources available that can help. Start with these:

The November 2018 Smithsonian magazine is a timely reminder of how racist and anti-Semitic attitudes like those of the El Paso and Pittsburg shooters can lead to acts of violence small and large. The issue also reinforces the importance of using stories to connect your students to Holocaust events.

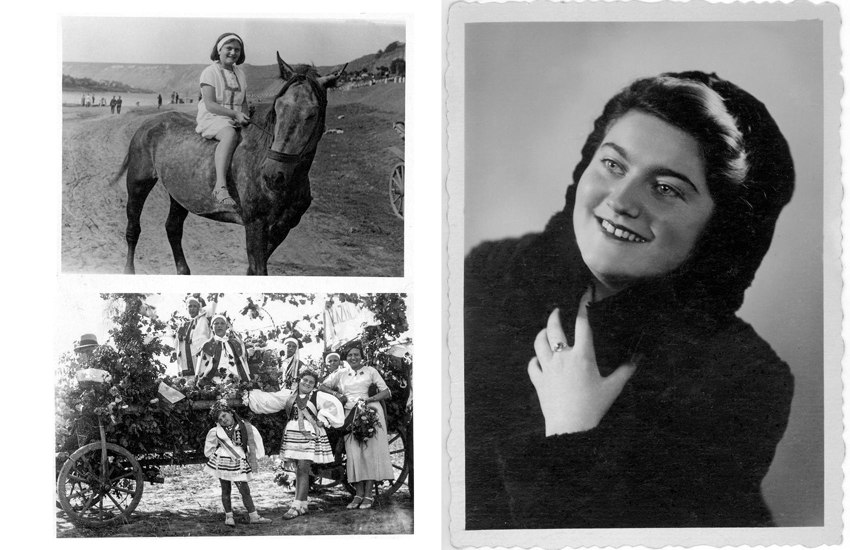

Five of the magazine’s articles focus on stories told by young people during the Holocaust and specifically on the story of Polish teenager Renia Speigal. Like Anne Frank in Holland, Renia also kept a diary describing life under the constant threat of death at the hands of the Nazi government. Recently discovered in a desk in New York City, Renia’s words have the power to resonate with your students and make the terrible events of that period real and accessible.

More than 65 diaries written by young people have surfaced from across Europe. In her article “World, Wake Up,” Alexandra Zapruder suggests that “these surviving fragments . . . are valuable beyond measure, endlessly surprising and complex accounts written inside the cataclysm itself.” She adds: “. . . nothing collapses the distance between the reader and the historical past quite like a diary.”

(Perhaps the most powerful article in the series is one written by Dara Horn. Horn challenges us and our students to remember not just Renia and Anne but to be aware of other accounts of the period as well. Simply reading Anne’s account can make it easier to ignore the people who shipped her away to be murdered and the fact that people like them are still around.

The Tree of Life synagogue shooter who admitted that he “wanted all Jews to die,” and the shooter in El Paso are not random concentration camp prison guards from the 1940s. They grew into what they are right here. Reading accounts beyond the inspirational such as Anne’s can help students better understand how that can happen.)

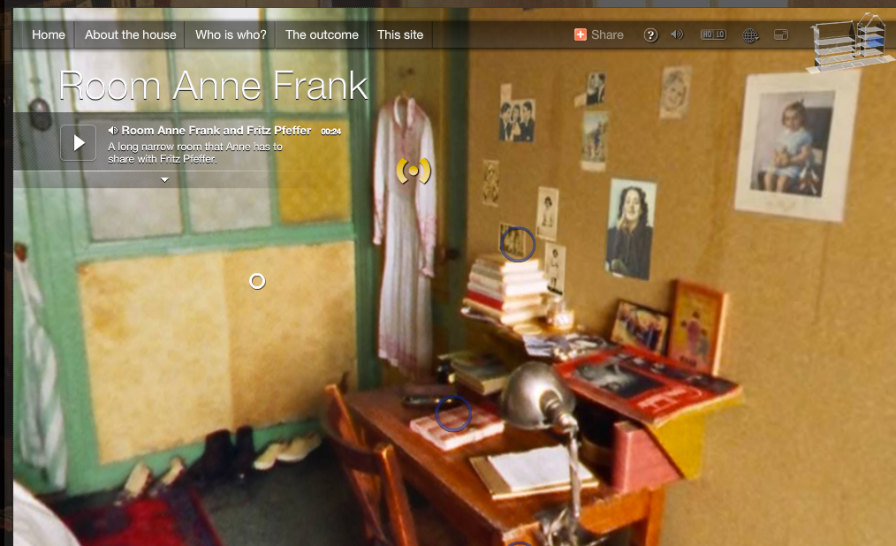

The Anne Frank House and the Anne Frank Center both provide a wide variety of resources that help tell individual stories. The 3D Secret Annex at The Anne Frank House can be especially powerful.

Using a variety of media, including text, audio, music, video clips, and 3D technology, the site takes you into the small area where Anne, her family, and four others hid for over two years. The site uses technology similar to VR apps – allowing you to walk around and through the Secret Annex as if you are Anne herself in 1942. During your exploring, you can hear descriptions of each area and pan around in 360 degrees. You can also let Anne take you on a tour, using period photographs and her own words from her diary. This piece is especially powerful because you get a sense of who Anne was and what she thought.

Use the this lesson plan to help your students explore the Annex with purpose. Download reader guides to Anne’s diary and explore extensive teaching resources including award winning Free2Choose curriculum materials.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is a must go-to when teaching about the Holocaust and other genocides around the world. Dig deeper into teaching about the Holocaust and then explore the USHMM lessons and commonly asked questions.

Get access to ten lesson plans with primary resources, materials, teaching suggestions from Echoes and Reflections.

The Anti-Defamation League has a ton of curriculum and professional development resources. Find their lessons here. Including a special section of resources specific to talking and teaching about the Pittsburg synagogue shooting.

USC Shoah Foundation has a rich database of video oral histories from survivors that can be connected to diary accounts such as Renia’s.

Teaching Tolerance has numerous resources for learning about the Holocaust, racism, and anti-Semitism. Be sure to explore a teaching kit titled One Survivor Remembers, a documentary around the oral history of Gerda Weissmann Klein. Get the Teacher’s Guide and primary sources.

The work of coming to terms with the past and connecting it to the present is at the heart of what you do every day. The alternative? Educational malpractice.

cross posted at glennwiebe.org

Glenn Wiebe is an education and technology consultant with 15 years' experience teaching history and social studies. He is a curriculum consultant for ESSDACK, an educational service center in Hutchinson, Kansas, blogs frequently at History Tech and maintains Social Studies Central, a repository of resources targeted at K-12 educators. Visit glennwiebe.org to learn more about his speaking and presentation on education technology, innovative instruction and social studies.