Helping Others Along – Motivation Theory and the SAMR Model

We cannot approach supporting our colleagues with a mindset that says “Ugh. They are doing it wrong!” perhaps followed by “AGAIN!” We must do our best to understand the context in which our colleagues operate, what motivates them to teach, and how we might serve them best.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“We awaken in others the same attitude of mind we hold toward them.”

Elbert Hubbard

As a second year teacher, I remember being very excited about leading my students to participate in a project-based learning activity. With great enthusiasm, I ran down the hall to see a teacher, much my senior, that I greatly respected and I wanted to share with him how excited I was. I was a bit taken aback and confused how negatively it was received. I soon realized that sometimes the things that we do with our students when they are a little out of the box can be perceived negatively by our colleagues. I realized that while enthusiasm can be infectious it is not by default, attractive to others.

Article continues belowAs innovators and early adopters of emerging technology we often find ourselves in the situation to help our colleagues. How do we best help them to understand the value of new technology and how it might benefit their students lives (rather than how might it help my fit into their classroom). How do we ask colleagues to adopt technology and help them to adapt the technology without putting our hands on their keyboard or their mouse and doing it for them. It’s important to adopt the sage wisdom of the old proverb: “If you fish for a man he will eat for a day, but if you teach a man to fish he’ll eat for the rest of his life.” This mantra in education particularly in adopting emerging technology is incredibly important. It is important that we help our colleagues to understand the value of the technology and how the technology can be used. This is best achieved through vicarious experience, guide-on-the-side coaching, and the right frame of thinking. We cannot approach supporting our colleagues with a mindset that says “Ugh. They are doing it wrong!” perhaps followed by “AGAIN!” We must do our best to understand the context in which our colleagues operate, what motivates them to teach, and how we might serve them best.

While we may be leading the adoption of innovation, we must take on the role of a guide, explaining to our colleagues where we are going, why we are going there, and what we hope to see when we arrive. It is easy for us to think “Save time, see things my way!” But this will not foster an innovative school culture. At times an innovator will have difficulty persuading those they know, after all an innovator is not without honor except within his home.

Innovation is an amplifier, it will amplify the good and bad of our teaching practice. Subconsciously, most of us recognize this amplification, which contributes to our fear over technology adoption. As champions we must learn to put ourselves in the shoes of a late adopter or laggard, then try to help them along. Empathetic understanding and leveraging real, meaningful relationships can not only promote adoption of innovation but can inspire for positive change.

The constant for all teachers is students and their learning needs. All teachers hope that they can make a difference is what can contribute to their decision to continue teaching.1 One researcher quoted a beginning teacher, as saying, “I’ll need a sense of success, not unqualified constant success, because I know that’s completely unrealistic. But, overall, you know, on average, that I’m making a difference for kids and that they’re learning from me.”1 The teacher’s desire to feel successful with his students was echoed by many of the teachers who chose to stay in the profession with their school community.1 A very healthy faculty room conversation would be about why we became teachers to begin with. I regularly encourage anyone in education to think about this as a reminder of who they are and how that informs the expectations they hold on themselves to prepare students for a different future.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

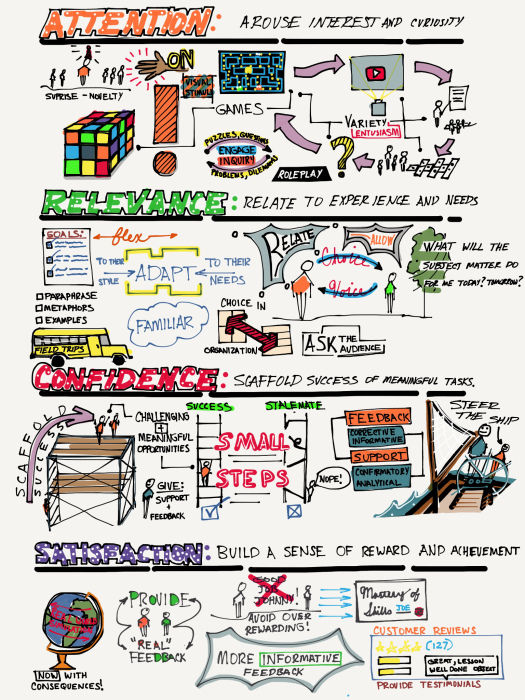

ARCS Model

There are certain key stages which are important to helping others to adopt emergent technology and innovativeness in general. These concepts can be conceptualized in the ARCS Model: Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction.2 Think if these as a process, starting with getting their attention and moving toward their satisfaction that they can do it.

Attention

When we relate the relevance of using emergent technology in the classroom we must describe how adoption is advantageous. Emergent technology can increase workflow efficiency for both teachers and students. For example, a paperless classroom takes time and energy to begin, but a teacher who makes over 100 copies a day might find themselves saving a significant amount of time if you consider the time it takes to stand by the copier over a year. Time savings and workflow efficiency are super important for educators but they need to see what you mean as well. Seeing others perform new, or threatening, activities without adverse consequences can generate expectations in observers that they too will improve if they intensify and persist in their efforts. Finally, in this first step, take into account your delivery style and method, newbies can easily conjure up fear-provoking thoughts about their ineptitude and can rouse themselves to elevated levels of anxiety that far exceed the fear experienced during the actual threatening situation. Take it easy, go slow.

Relevance

The adoption anything new must first be framed by something old, something familiar, and then advantages should be explained. For people to try new things and begin to adopt innovation, they general frame their understanding around how it relates to their previous practice and that they feel a need/problem. For example, VCRs allowed us to record, play, fast-forward and rewind, but the tape was not usable after many showings and sometimes the tape ripped. DVDs allowed us to also record, play, fast-forward and rewind but the digital quality remained constant… unless you scratched your DVDs. YouTube videos can be recorded (added to a playlist), played, fast-forwarded, rewound, they do not lose their quality and we can upload or own. Thus the advantage of using YouTube is framed around our past adoption. When we take the time to persuade our colleagues about adoption we are providing them with context-based application effective action which makes them more likely to mobilize greater effort than those who are not persuaded, but told.

Confidence

“The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.” — Michelangelo

Emergent technology can be pretty complex, to be told that things are going to change every 6 to 18 months3 can be overwhelming to those who have yet to embrace innovativeness. We need to help people to aim high by creating a safe environment to try new things. When we work with colleagues they must feel comfortable to fail in front of you and learn with you (guide-on-the-side). We know that failure is the greatest teacher, but we are so afraid of it! Through a productive struggle, we can help our colleagues to personal mastery experiences with something new. Leveling the difficulty of the task will allow for early successes which yield increased attempts at more difficult tasks later on and eventually leading to a decision to adopt.

Satisfaction

What does it mean to be successful at adoption? What does it mean to do something right or correctly? A teacher’s efficacy belief is a judgment of his or her capabilities to bring about desired outcomes of student engagement and learning.4 Research has shown that a teacher’s efficacy is related to how teachers’ decisions are made, how goals are shaped, how planning and organization are implemented, and how teachers react in the classroom and relate to students.4 In addition, teachers with high self-efficacy embrace new ideas and methods for teaching.4 In developing a favorable or unfavorable attitude toward an innovation, an individual may mentally apply the new idea to his or her present or anticipated future situation before deciding whether or not to try it.5 The strength of people’s convictions in their own effectiveness is likely to affect whether they will even try to cope with given situations.6 Satisfaction resides in the willingness of the teachers being studied to adopt the technology and apply it to their professional settings.

SAMR Model

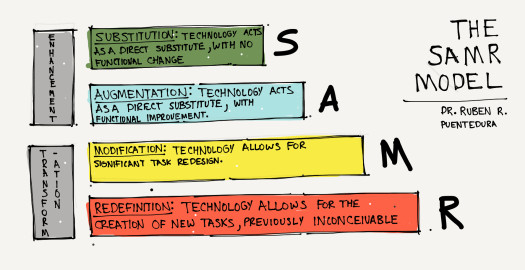

One of the most powerful ways to have a discussion with colleagues regarding technology adoption and pedagogical-shift strategies is the SAMR Model.

[Game-Based Learning Yields Empathetic Understanding]

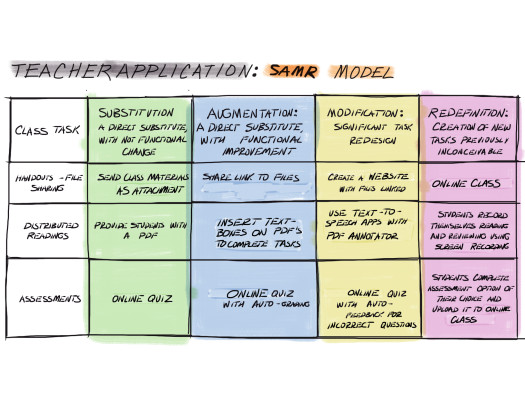

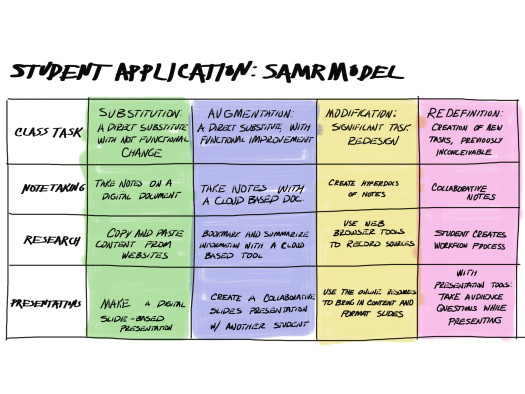

We start by Substituting our existing strategies for one that are supported by emergent technology, we then Augment the strategy when we find that technology can improve (rather than replace) the strategy, next we use technology to Modify the strategy, and finally we Redefine the entire strategy when we find technology may offer us a better way of doing things. Simply put, the SAMR Model helps each of us to rethink individual lessons, units, and instructional practice. For example, we can take a paper worksheet-packet, make it digital, then use tools to annotate on it, then redesign the activity with a slide deck or video, and finally we create a brand new activity, different from where we started. For the teacher and student workflow SAMR might look like these examples 8:

Professional Development: Designing, Developing, and Implementing

Professional Development offerings can be the catalyst of positive change. We have spent a great deal of time in this book discussing adopters and who we are in the story. Understanding ourselves and our colleagues can yield context-based, empathetically considerate, professional development opportunities.

A combination of the SAMR Model and the ARCS Model are excellent for developing professional development offerings. When planning a training session there are a few things from the ARCS model to consider…

- Attention: arouse interest and curiosity

- Described:

- Stimulate perceptions (surprise, uncertainty, novelty, juxtapositions).

- Engage inquiry (puzzles, questions, problems, dilemmas).

- Create variety (different kinds of examples, models, exercises, and presentation modalities).

- Examples:

- incongruity, conflict

- games, roleplay

- hands-on/minds-on methods

- questions, problems, brainstorming

- videos, mini-discussion groups, lectures, visual stimuli, storytelling

- Reflection: How does an instructional leader’s enthusiasm change attention?

- Described:

- Described:

- Stimulate perceptions (surprise, uncertainty, novelty, juxtapositions).

- Engage inquiry (puzzles, questions, problems, dilemmas).

- Create variety (different kinds of examples, models, exercises, and presentation modalities).

- Stimulate perceptions (surprise, uncertainty, novelty, juxtapositions).

- Engage inquiry (puzzles, questions, problems, dilemmas).

- Create variety (different kinds of examples, models, exercises, and presentation modalities).

- Examples:

- incongruity, conflict

- games, roleplay

- hands-on/minds-on methods

- questions, problems, brainstorming

- videos, mini-discussion groups, lectures, visual stimuli, storytelling

- incongruity, conflict

- games, roleplay

- hands-on/minds-on methods

- questions, problems, brainstorming

- videos, mini-discussion groups, lectures, visual stimuli, storytelling

- Reflection: How does an instructional leader’s enthusiasm change attention?

- Relevance: relate to experience and needs

- Described:

- Allow audience to select or define goals, give examples of goals, discuss value of goals.

- Adapt to what the audience wants to cover or how to cover it

- Use familiar communication modalities, relate goals to something familiar such as prior knowledge or experiences

- Examples:

- paraphrase content, use metaphors, give examples

- ask audience to give examples from their own experiences

- give audience choice in how to organize what they learn, explain how the new learning will use students’ existing skills,

- explain or show “What will the subject matter do for me today?…tomorrow?”

- Reflection: Reflection: How do teaching models, field trips, portfolios, and student choice change relevance?

- Described:

- Described:

- Allow audience to select or define goals, give examples of goals, discuss value of goals.

- Adapt to what the audience wants to cover or how to cover it

- Use familiar communication modalities, relate goals to something familiar such as prior knowledge or experiences

- Allow audience to select or define goals, give examples of goals, discuss value of goals.

- Adapt to what the audience wants to cover or how to cover it

- Use familiar communication modalities, relate goals to something familiar such as prior knowledge or experiences

- Examples:

- paraphrase content, use metaphors, give examples

- ask audience to give examples from their own experiences

- give audience choice in how to organize what they learn, explain how the new learning will use students’ existing skills,

- explain or show “What will the subject matter do for me today?…tomorrow?”

- paraphrase content, use metaphors, give examples

- ask audience to give examples from their own experiences

- give audience choice in how to organize what they learn, explain how the new learning will use students’ existing skills,

- explain or show “What will the subject matter do for me today?…tomorrow?”

- Reflection: Reflection: How do teaching models, field trips, portfolios, and student choice change relevance?

- Confidence: scaffold success of meaningful tasks

- Described:

- Set clear goals, standards, requirements, & evaluative criteria.

- Give challenging & meaningful opportunities for successful achievement within available time, resources, & effort

- Encourage personal control, show or explain how effort determines success (personal responsibility = achievement).

- Examples:

- allow audience to choose goals

- allow small steps for achievement

- give feedback & support

- provide learners with some degree of control over their learning & assessment

- show that success is a direct result of personal effort

- give confirmatory-corrective-informative-analytical feedback rather than social praise

- Reflection: Reflection: How do clear organization and easy to use materials change expectations for success?

- Described:

- Described:

- Set clear goals, standards, requirements, & evaluative criteria.

- Give challenging & meaningful opportunities for successful achievement within available time, resources, & effort

- Encourage personal control, show or explain how effort determines success (personal responsibility = achievement).

- Set clear goals, standards, requirements, & evaluative criteria.

- Give challenging & meaningful opportunities for successful achievement within available time, resources, & effort

- Encourage personal control, show or explain how effort determines success (personal responsibility = achievement).

- Examples:

- allow audience to choose goals

- allow small steps for achievement

- give feedback & support

- provide learners with some degree of control over their learning & assessment

- show that success is a direct result of personal effort

- give confirmatory-corrective-informative-analytical feedback rather than social praise

- allow audience to choose goals

- allow small steps for achievement

- give feedback & support

- provide learners with some degree of control over their learning & assessment

- show that success is a direct result of personal effort

- give confirmatory-corrective-informative-analytical feedback rather than social praise

- Reflection: Reflection: How do clear organization and easy to use materials change expectations for success?

- Satisfaction: build a sense of reward and achievement

- Described:

- Support learning applied in real-world or simulated context with consequences

- Provide feedback after practice to confirm, analyze, or correct performance

- Apply consistent consequences for meeting standard consistent evaluation criteria

- Examples:

- avoid over-rewarding easy tasks,

- give more informative feedback rather than praise or entertainment value

- use practical examples related to audience interests award certificates for mastery of skills

- provide testimonials from previous audience about value of the learning

- give evaluative feedback using equitable criteria

- Reflection: Reflection: Why does social praise not work as well as informative feedback in creating satisfaction? How do rubrics change satisfaction?

- Described:

- Described:

- Support learning applied in real-world or simulated context with consequences

- Provide feedback after practice to confirm, analyze, or correct performance

- Apply consistent consequences for meeting standard consistent evaluation criteria

- Support learning applied in real-world or simulated context with consequences

- Provide feedback after practice to confirm, analyze, or correct performance

- Apply consistent consequences for meeting standard consistent evaluation criteria

- Examples:

- avoid over-rewarding easy tasks,

- give more informative feedback rather than praise or entertainment value

- use practical examples related to audience interests award certificates for mastery of skills

- provide testimonials from previous audience about value of the learning

- give evaluative feedback using equitable criteria

- avoid over-rewarding easy tasks,

- give more informative feedback rather than praise or entertainment value

- use practical examples related to audience interests award certificates for mastery of skills

- provide testimonials from previous audience about value of the learning

- give evaluative feedback using equitable criteria

- Reflection: Reflection: Why does social praise not work as well as informative feedback in creating satisfaction? How do rubrics change satisfaction?

In an effort to understand why teachers continue to teach in a challenging career I once conducted a survey of 75 Middle School teachers asking them to identify why they stayed in their profession.13I was looking for attributes about success and I had tributes that they identified that set them apart. But what I found was many of them valued relationships with their colleagues more than most other outside factors. These findings are parallel with teachers who were identified in a federal study on teacher mobility as “movers” or “leavers” described teaching in isolation as one factor that contributed to their dissatisfaction. Movers left the schools where they worked in isolation for schools where colleagues interacted and shared ideas for teaching. Those teachers, titled “settled stayers”, described their supportive colleagues as a reason for their decision to stay at their school.1 Studies on the impact of colleague support on the retention of teachers have found those beginning teachers provided a common planning time with colleagues and a scheduled time to interact with colleagues on instructional issues had a 42% less likelihood of leaving as opposed to staying and a 25% less likelihood of moving as opposed to staying.9 Through my experiences working with schools, I found that directors of technology and key decision-makers seeking to roll out emerging technology, find a great deal of success when they have themselves positive relationships with their colleagues and with their employees. Our social-connectiveness is very important.

But let’s focus on boots and the ground, let’s focus on working side-by-side as a coach, as a guide, as a trainer, and more importantly, as a friend to our colleagues who have a little bit of difficulty adopting new technologies. Professional Development in education has the responsibility of promoting teacher growth in a valid and practical manner. A community of teacher-learners can effectively promote this growth beyond what simple in-servicing (alone) can accomplish. Workshop and other in-service events are magnified by collaborative, shared-experiences. As teaching professionals we need to learn, share, and collaborate with their peers, we need to feel successful and believe in our ability to succeed.

Our work as champions of innovation must be informed by the best practices examples provided through peer coaching and mentorship programs which can be high effective, when they provide collaborative atmospheres. Like championing a cause, mentoring is a professional role that requires professional renewal, enhanced self-esteem, more reflective practice, and leadership skills. The knowledge and skills that experienced teachers acquire as part of mentor training and practice is continual professional growth.10 When mentoring is viewed as a peer coaching requiring teachers to plan, demonstrate, and practice new instructional practices in a collaborative manner, schools may find less fragmentation, less teacher isolation.11 As we discussed previously, if you are alone in your professional journey, you are doing it wrong. Mentoring programs for teachers should serve to offer deliberate psychological and professional development conditions necessary for the development of teacher knowledge, skills, and dispositions, thus increasing teacher retention through effective, efficient mentoring. Champions, mentors, and peer coaches must develop their understanding of building helping relationships, effective teaching practices, effective coaching practices, and how to work with adults.12

As we think beyond working with one colleague at a time, we must begin to think about developing our culture. The best practices found in effective professional learning communities (PLCs) can help us significantly. PLCs can be defined at multiple levels (local, state, national, and international) in multiple contexts (team of teachers, building staff, school district of teachers, group of common content teachers, etc…) yet the focus of every PLC must be to explore three major questions: What do we want each student to learn? How will we know when each student has learned it? How will we respond when a student experiences difficulty in learning?14

There are five major attributes of PLCs:

- Supportive and Shared Learning – the collegial and facilitative participation of the principal, who shares leadership (and power/authority) through inviting staff input in decision making.

- Collective Learning – application of collective learning to address student needs.

- Shared Values and Vision – a shared vision that is developed from the teachers’ commitment to student learning.

- Supportive Conditions – time scheduled for teachers to come together to learn, make decisions, problem solve, and create work exemplified by collaboration.

- Shared Personal Experience – a peers helping peers process, based on a desire for individual and community improvement founded in mutual respect and trustworthiness of the teachers involved.

These five major attributes are reflective of Bandura’s (1977)6 performance accomplishment, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion and emotional arousal. Clearly the research shows repetitive themes in community building and job satisfaction for teaching professionals.

The teaching can be a lonely profession complete with isolation and the close-my-door-and-teach mentality. Yet, the wealth of knowledge and experience that can be accessed through well structured professional development and collaboration opportunities. This takes effort on the part of the teachers, administrators, and institutions of learning, but the effort will yield positive results. The Reciprocal Nature of Inspiration: Inspiring Others Will Inspire You.

Image Credit: Chris Stein, a superstar Teacher, and illustrator Extraordinaire!

Source Notes (in order of use)

- Johnson, S.M. & Birkeland, S.E. (2003). Pursuing a “sense of success”: New teachers explain their career decisions, American Educational Research Journal 40 (3) (2003), pp. 581–617.

- Keller, J. (1987) Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction are developed in John Keller’s ARCS model of motivational design.

- “Moore’s Law – Investopedia.” https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/mooreslaw.asp. Accessed 18 Apr. 2018.

- Tschannen-Moran, M. & Hoy, A.W. (2001) Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct, Teaching and Teacher Education 17 (2001), pp. 783–805.

- Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free, 2003. Print.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review 84 (2), 191-215.

- Puentedura, R. The SAMR Model http://hippasus.com/resources/sweden2010/SAMR_TPCK_IntroToAdvancedPractice.pdf

- Based on: Schrock, K (2013) “SAMR – Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Everything.” 9 Nov. 2013, http://www.schrockguide.net/samr.html. Accessed 20 Apr. 2018.

- Smith, T.M. & Ingersoll, R.M. (2004). What are the effects of induction and mentoring on beginning teacher turnover?, American Education Research Journal 41 (3) (2004), pp. 681–714.

- Hanson, S (2010). What Mentors Learn About Teaching. Educational Leadership, 67 (8) 2010, 76-80

- Reiman, A.J. & DeAngelis Peace, S. (2002) Promoting Teachers’ Moral Reasoning and Collaborative Inquiry Performance: a developmental role-taking and guided inquiry study. Journal of Moral Education, 31(1), 51-66.

- Dotger, B. & Reiman, A. 2006-01-26 “Measuring Fidelity and Concerns in the Process of Implementing an Innovation” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education Online. <PDF> 2009- 05-25 fromhttp://www.allacademic.com/meta/p36187_index.html

- Shippee, M. & Dotger, B. (2010) Perceptions of Success for Teachers: The Role of Mentor Programs. (unpublished).

- DuFour, R. (2004) What is a “Professional Learning Community”? Schools as Learning Communities. Educational Leadership 61(8)

- Hord, S. M. (1997) Professional Learning Communities: What Are They and Why Are They Important. Issues… about change. 6 (1). Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL) Austin, Texas

cross posted at micahshippee.com

Micah Shippee, PhD is an out-of-the-box-doer, a social studies teacher, and a technology trainer. He works to bridge the gap between research and practice in the educational sector. Micah explores ways to improve motivation in the classroom and seeks to leverage emergent technology to achieve educational goals. As an innovative "ideas" person, Micah likes to think, and act, outside the box. Micah is motivated and energetic, taking a creative approach towards achieving goals. As an Educational Consultant, and Keynote Speaker, he focuses on the adoption of emergent technology through the development of an innovative learning culture. Micah believe that innovativeness is the pedagogy of the future.