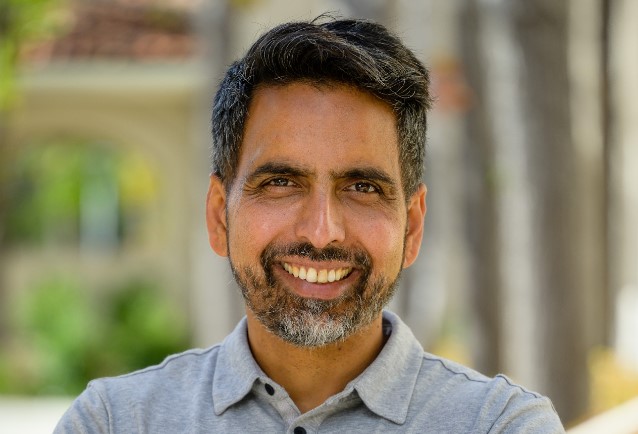

Here’s What We Should Take Away From PISA Math Score Drop, Says Sal Khan

The latest PISA results showed U.S. Math scores plummeting but the real story is both more bleak and positive, says Sal Khan.

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sal Khan isn’t surprised by the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) math results for U.S. students, which were recently released and contained more pluses than minuses.

“If I had made a guess, I would have probably gotten pretty close to what the PISA results are showing,” says Khan, founder of the free online learning platform Khan Academy.

The PISA 2022 results, which are compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), paint a grim picture of math education with 15-year-old U.S. students seeing a 13-point drop from 2018, the last time the test was administered, and falling behind other industrialized countries.

The U.S. held steady in reading and science, while among the 81 international school systems that participated in PISA, it rose from 29th in math achievement in 2018 to 26th in 2022, primarily due to other countries seeing an even greater slide. However, that was little comfort given the cold reality of U.S. math scores overall.

Khan's takeaways from the test results are more nuanced – in both positive and negative ways – than some alarmist reactions to the results.

PISA Scores Aren’t Entirely Fair to The U.S.

Many headlines about the PISA scores portray the results as a disaster, and while it certainly is not good, Khan says the reality of the results are more complicated.

“When people say, ‘Oh the U.S. is 26th [in math], how can that be, we spend so much money,’ I don't think it's completely fair to the U.S.,” says Khan. “If you truly compared us to large, diverse countries — diverse in every way, shape or form — we’re doing alright. And there are pockets in the U.S. that would be at the very top of that ranking. And when I say pockets, not even just individual schools or districts, I’m talking about the state of Massachusetts, which would be near the top of that ranking if it was an independent country.”

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

Still, There’s A Problem With Math Education in The U.S. and It’s Actually Bigger Than The PISA Results Show

On the other hand, Khan believes the small gains or drops in PISA scores and questions about which country’s school systems did what in the pandemic distract from the larger long-term issues with math education in the U.S.

“On some level, these tests that show like, ‘We've gone up or down by five points’ -- it's almost like the house is burning, and you realize that your sliding door is creaking,” Khan says.

For instance, if you look closely at NAEP math test results, the story of the last few years is less dramatic, though the long-term trend remains disturbing.

“Pre-pandemic, in Detroit 6% of kids were at grade level or above. Post-pandemic 3%,” Khan says. “ So one narrative is like ‘Oh the pandemic was horrible, it reduced the number of kids at grade level by 50%.’ But guess what, 94% were at grade level to begin with. That's the house burning part.”

Remedial Math is A Euphemism

The state of U.S. math education becomes even more grim when considered in another way: The vast majority of college students have to take remedial math.

“Remedial math is a euphemism for seventh-grade math,” Khan says. And of course, many of the students who go on to college are those students who do better overall in school. “These students go through these motions, they take 12-13 years of regular schooling. They’ve taken Algebra 1 and Algebra 2. Some have taken trig and calculus,” Khan says. But these lessons are not sticking.

However, the good news is there are effective, evidence-based methods for teaching math. “I'm 100% sure that anyone who can learn how to read is capable of learning college algebra by the time they graduate college,” Khan says.

Ways To Improve Math Scores

One way that Khan says math scores can be improved is by having students use a learning platform such as Khan Academy a little bit every week. He knows that can sound self-serving but points out he doesn’t get paid more if more people take advantage of a nonprofit education platform. “If anything, I have to raise more money if more people use Khan Academy,” he says. He truly believes in its power to help students and has the data to back it up.

“If students are able to put in even 30 to 60 minutes per week, 18 hours over a year, those students are accelerated something between 20% and 80%, depending on the grade level, depending on the study,” he says. “Broadly speaking, it's probably around 30%. In places like Khan Lab School and Khan World School, where the kids are doing 30 minutes per day, you're seeing two grade levels a year [acceleration].”

Khan encourages educators and parents to take advantage of these resources as he formally believes doing so will add up to math success. He says, “If we had a world where students learned college algebra by the 12th grade, that one thing alone would be transformative.”

Erik Ofgang is a Tech & Learning contributor. A journalist, author and educator, his work has appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Associated Press. He currently teaches at Western Connecticut State University’s MFA program. While a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine he won a Society of Professional Journalism Award for his education reporting. He is interested in how humans learn and how technology can make that more effective.