From Coding to Coding:

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As we saw from the many sessions about coding during ISTE 2015, the topic of programming computers is back in fashion. Way back when, computers had been tools used only by scientists and hobbyists, but personal computers changed everything. PCs took commands from anyone who knew how to communicate with them. We could type on the keyboard and watch the monitor for the results (and hope for the best). No more punch cards, greybar printouts (with or without fatal errors), or time-sharing.

We communicated with these machines by programming or coding—writing the line-by-line instructions that told the computer what to do. The language we used was BASIC, an acronym for Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code.

In schools, we debated what computers were good for, and at first the answer was programming. Microcomputers usually shipped with BASIC installed and it was easy to learn. In the early 1980s, Radio Shack offered teachers free classes in BASIC programming. I signed up—and the rest is history. I could tell a computer what to do and it would do it. Imagine!

I wrote a grant proposal for a classroom full of TRS-80s. My idea was to teach students the logic of BASIC programming and transition to the logic of writing compositions. They would learn the very latest workplace skills at the same time. I received the grant and the room full of machines but never had the chance to implement the concept. Instead, I taught process writing with a word processor. Other teachers embraced programming and wrote their own software.

The very first issue of Classroom Computer News (CCN) in 1980 celebrated programming. Jeff Nilson wrote, “The computer tantalizes teachers. Good software could free them from much of the drudgery involved in teaching basic skills while at the same time making it fun for kids to learn the skills.”

He designed Gramaze, a game to help students identify direct objects in sentences. CCN published the program listing so that other teachers could enter it and use the program with their students too.

That issue of CCN also had a review of Step by Step, a program to teach BASIC. Lessons advanced from teaching students a simple PRINT “Hi” through arrays and graphics to complex programs. The verdict: “This is the kind of educational programming that personal computing needs more of.”

Tools and ideas to transform education. Sign up below.

While the point was to create software, learning to program had its own merits. Logo, a programming language for students, used turtle graphics. Students wrote instructions and the turtle moved. Advocates like MIT’s Seymour Papert said it encouraged children to think and solve problems. They could understand, predict, control, and reason about the turtle’s motion. These Piagetian-based theories promoted a constructivist approach to learning.

Teaching programming went in and out of favor over the years and a robust software industry grew out of programs that were too sophisticated for teachers or children to create. Classroom Computer Learning reviewed software and gave awards each year to the best programs. In 1989, the editors said, “One of the most interesting things we learn from our software awards each year is where the market is going. Here’s what we learned this year:

■ Speech is in—a number of new programs use speech capabilities—digitized and synthesized.

■ Tools are stronger than ever—our judges think these kinds of programs hold much potential for use in the classroom.

■ Multimedia is on the brink. An interactive video game won an award for the first time.

■ Drill and practice is back (but only if it’s great).”

In 1994, T&L editors observed trends in that year’s collection of winning programs. One of their key conclusions was that “Software is increasing in complexity, requiring more computer memory and sophisticated machines.” (Note that this meant the programs needed a minimum of 4 MB of RAM and a 386 or faster processor.)

T&L’s focus in 1994 was on telecommunications and looking ahead to the “much heralded” information superhighway that promised to take the Internet broadband.

For the third year in a row, T&L’s October 1995 cover article focused on the Internet. But this issue was all about the new World Wide Web, which was causing a major stir in schools. Four months later, T&L launched its own Web site, www.techlearning.com.

The Web was the next new thing. By 1998 T&L had expanded techlearning.com to put more content online and publish articles for educators about practical classroom applications, edtech recommendations, and advice for navigating and understanding the rapidly changing world of technology.

In-depth articles explored topics such as teaching students to be savvy media critics, designing effective AUPs, and tapping into “virtual school” experiences.

By 2000, schools wanted to be on the Web. So educators started coding in HTML or used interfaces one step away from writing the code itself.

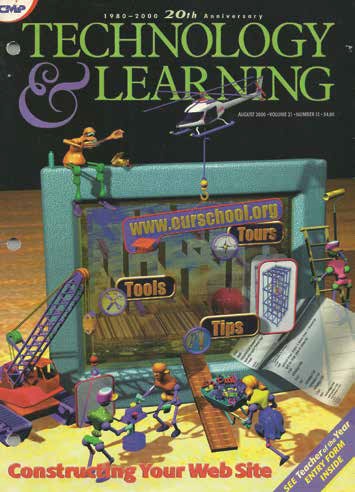

In August 2000, T&L ran advice on constructing a Web site. The issue included a “Web Builders’ Toolbox” with the latest authoring, graphics, and hosting tools to help schools and districts build an A+ Web site. Kathy Schrock provided tips for “Building a Content-Rich School Web Page.” And we took readers on a tour of different school sites to illustrate what was possible when students and teachers worked together to create an online presence. (Image: August 2000 cover.)

Every month during the 2000s, techlearning.com offered Web tours of sites in specific subject areas and a “Site of the Day.” Educators used educational Web sites for teaching and learning and also created their own sites.

Business applications have always been popular in schools. At first there were stand-alone word processors like Scripsit and Bank Street Writer and spreadsheets like VisiCalc. Then Microsoft bundled its programs and schools could get writing, number crunching, presentation, and even communications programs in a single package.

Eventually software moved online. Although we can still work with software on computers, we’re just as likely to do our processing in the cloud. Google Apps—and millions of other apps—are everywhere our personal device is. Today most people are generally more inclined to text and tweet and use social media than they are to email or call.

Apps are in, and a whole new industry has grown around them. Apps are the latest thing and young people are already part of the trend. Speaking of trends brings us back to coding. We mentioned above a 1980 review of Step by Step, a program to teach BASIC. In the past year, techlearning.com has published mini-reviews of CodeMonkey, a site for children to learn programming skills, Codecademy, a site with hands-on coding practice and live feedback, Kodable, an introductory programming logic app, and more. The reviews indicate that students are developing logic, reasoning, and problem-solving skills.

And then there’s Kojo—a graphical environment that uses computer programming for self-directed, interactive learning through exploration and discovery. Kojo is partly based on ideas from Logo.

The more things change, the more they end up the same.

Gwen Solomon was senior analyst at the US Department of Education, director of The Well Connected Educator, and is the author of several books on edtech, including Web 2.0: How-to for Educators. She has been a contributing editor for Tech & Learning since 1998.

Gwen Solomon was Founding Director of The School of the Future in New York City, Coordinator of Instructional Technology Planning for New York City Public Schools, and Senior Analyst in the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Instructional Technology. She has written and co-authored several books and many magazine articles on educational technology.